Abstract

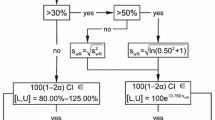

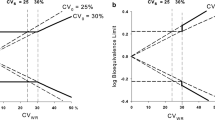

Bioequivalence studies are performed to demonstrate in vivo that two pharmaceutically equivalent products (in the US) or alternative pharmaceutical products (in the EU) are comparable in their rate and extent of absorption. By definition, for highly variable drugs (HVDs), the estimated within-subject variability is >30%. HVDs often fail to meet current regulatory acceptance criteria for average bioequivalence (ABE). The determination of the bioequivalence of HVDs has been a vexing problem since the inception of the current regulations. It is of concern not only to the generic industry but also to the innovator industry. This article reviews the definition of HVDs, the present regulatory recommendations and the approaches proposed in the literature to deal with the bioequivalence problems of HVDs. The approach of scaled ABE (SABE) is proposed as the most adequate procedure to solve the problem. It is demonstrated that SABE has firm theoretical foundations. In fact, statistical tests similar to SABE are used in various fields, such as psychology and quality control. Algorithms and numerical examples are presented to calculate SABE from the data in conventional two-period and replicate-design studies. The most important feature of SABE is that a fixed sample size is adequate to demonstrate bioequivalence regardless of within-subject variability. The conditions for reaching consistent regulatory decisions with SABE are discussed. The required sample size, for a given statistical power, depends on the regulatory criteria. Sample sizes with different criteria are demonstrated and compared with those arising from a recent informal US FDA proposal.

Pragmatic considerations lead to modifications of the theoretical concept of SABE. Several modifications are proposed, including reference scaling, restriction on the estimated geometric mean ratios and possibly limiting SABE to only secondary bioequivalence metrics such as the maximum concentration. Each proposal has its own merit but is also a source of new controversy. Overall, the statistical evaluation of SABE is more complex than that of ABE, which means higher regulatory burden. Standardized open software could be very useful in this regard. A small program script is presented to calculate SABE confidence limits.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Division of Bioequivalence, Office of Generic Drugs, US FDA Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. Statistical procedures for bioequivalence studies using a standard two-treatment crossover design. Rockville (MD): US FDA, 1992

Blume HH, Midha KK. Bio-International 92 Conference on Bioavailability, Bioequivalence, and Pharmacokinetic Studies. J Pharm Sci 1993; 82(11): 1186–9

Blume H, McGilveray I, Midha K. Bio-International 94 Conference on Bioavailability, Bioequivalence and Pharmacokinetic Studies. Eur J Pharm Sci 1995; 3(2): 113–24

Midha KK, Nagai T. Bioavailability, bioequivalence and pharmacokinetic studies: FIP Bio-International ′96 (1996 Tokyo, Japan). Tokyo: Business Center for Academic Societies Japan, 1996

Haidar SH, Davit B, Chen ML, et al. Bioequivalence approaches for highly variable drugs and drug products. Pharm Res 2008; 25(1): 237–41

European Medicines Agency [EMEA] Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use [CHMP]. Concept paper for an addendum to the note for guidance on the investigation of bioavailability and bioequivalence: evaluation of bioequivalence of highly variable drugs and drug products [document reference EMEA/CHMP/EWP/147231/2006]. London: EMEA, 2006

Davit BM, Conner DP, Fabian-Fritsch B, et al. Highly variable drugs: observations from bioequivalence data submitted to the FDA for new generic drug applications. AAPS J 2008; 10(1): 148–56

Midha KK, Rawson MJ, Hubbard JW. The bioequivalence of highly variable drugs and drug products. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther 2005; 43(10): 485–98

Shah VP, Yacobi A, Barr WH, et al. Evaluation of orally administered highly variable drugs and drug formulations. Pharm Res 1996; 13(11): 1590–4

Davit BM. Highly variable drugs: FDA case studies. Advisory Committee for Pharmaceutical Sciences, Office of Generic Drugs, US FDA Center for Drug Evaluation and Research [online]. Available from URL: http://www.fda.gov/ohrms/dockets/ac/04/slides/4034S2_06_Davit.ppt. [Accessed 2008 Nov 17]

Tanguay M. Technical update: bioequivalence design issues. Monte Carlo: Systemic Products, 2006

Martinez M, Langston C, Martin T, et al. Challenges associated with the evaluation of veterinary product bioequivalence: an AAVPT perspective. J Vet Pharmacol Therap 2002; 25: 201–20

Schuirmann D. A comparison of the two one-sided tests procedure and the power approach for assessing the equivalence of average bioavailability. JPharmacokin Biopharm 1987; 15: 657–80

Hauschke D, Steinijans V, Pigeot I. Bioequivalence studies in drug development: methods and applications. Chichester: Wiley, 2007

Tanguay M. Bioequivalence requirements: key differences within Europe and between EMEA, FDA and HPFB [online]. Available from URL: http://www.anapharm.com/site/upload/site/Generateur/Prague_IIR_MTanguay_Sept%2014%202005.pdf [Accessed 2008 Nov 17]

Ducharme MP, Potvin D. Understanding bioequivalence: the experience of a global contract research organization. Pharmagenerics 2003 Sep; 53-60 [online]. Available from URL: http://www.touchbriefings.com/cdps/cditem.cfm?NID=15#Bioequivalence [Accessed 2009 Sep 14]

DiLiberti CE. BE for highly variable drugs: an industry perspective [online]. Available from URL: http://www.aapspharmaceutica.com/meetings/files/90/21DiLiberti.pdf [Accessed 2008 Nov 17]

Benet L. Bioavailability and bioequivalence: definitions and difficulties in acceptance criteria. In: Midha KK, Blume HH, editors. Bio-International 2: bioavailability, bioequivalence and pharmacokinetics. Stuttgart: Medpharm, 1993: 27–35

Benet L. Individual bioequivalence: an overview paper presented at AAPS International Workshop on Individual Bioequivalence: Realities and Implementation 1999; Montreal (QC)

Blume HH. “One-size-fits-all” in bioavailability and bioequivalence testing. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther 2009; 47(7): 419–20

Tsang YC, Pop R, Gordon P, et al. High variability in drug pharmacokinetics complicates determination of bioequivalence: experience with verapamil. Pharm Res 1993; 13(6): 846–50

Tothfalusi L, Speidl S, Endrenyi L. Exposure-response analysis reveals that clinically important toxicity difference can exist between bioequivalent carbamazepine tablets. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2008; 65(1): 110–22

Wellek S. Testing statistical hypotheses ofequivalence. London: Chapman & Hall, 2003

Lehmann E. Testing statistical hypotheses. New York: John Wiley and Sons, 1959

Sheiner LB. Bioequivalence revisited. Stat Med 1992; 30: 1777–88

Schall R, Williams RL. Towards a practical strategy for assessing individual bioequivalence. Food and Drug Administration Individual Bioequivalence Working Group. J Pharmacokin Biopharm 1996; 24(1): 133–49

Schall R, Luus H. On population and individual bioequivalence. Stat Med 1993; 12: 1109–24

Anderson S, Hauck WW. Consideration of individual bioequivalence. J Pharmacokin Biopharm 1990; 18(3): 259–73

Rom DM, Hwang E. Testing for individual and population equivalence based on the proportion of similar responses. Stat Med 1996; 15(14): 1489–505

US FDA Center for Drug Evaluation and Research [CDER]. Statistical approaches to establishing bioequivalence: guidance for industry. Rockville (MD): CDER, 2001

US FDA Center for Drug Evaluation and Research [CDER]. Bioavailability and bioequivalence studies for orally administered drug products: general considerations. Guidance for industry. Rockville (MD): CDER, 2003: 1–46

Steinijans V, Hartmann M, Huber R, et al. Lack of pharmacokinetic interaction as an equivalence problem. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther Toxicol 1991; 29(8): 323–8

US FDA Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research [CBER]. Guidance for industry: drug interaction studies: study design, data analysis, and implications for dosing and labeling. Rockville (MD): CBER, 2006

US FDA Center for Drug Evaluation and Research [CDER]. Food-effect bioavailability and fed bioequivalence studies. Rockville (MD): CDER, 2002

Health Canada. Guidance for industry: conduct and analysis of bioavailability and bioequivalence studies. Part A: oral dosage formulations used for systemic effects. Ottawa (ON): Health Canada, 1992

European Medicines Agency [EMEA] Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use [CHMP]. Note for guidance on the investigation of bioavailability and bioequivalence. London: EMEA, 2001: 1–22

Blume HH, Elze M, Potthast H, et al. Practical strategies and design advantages in highly variable drug studies: multiple dose and replicate administration design. In: Blume HH, Midha KK, editors. Bio-International 2: bioavailability, bioequivalence and pharmacokinetics. Stuttgart: Medpharm, 1994

Schug BS, Elze M, Blume HH. Bioequivalence of highly variable drugs and drug products: steady state studies. In: Midha KK, Nagai T, editors. Bioavailability, bioequivalence and pharmacokinetic studies: FIP Bio-International ′96 (1996 Tokyo, Japan). Tokyo: Business Center for Academic Societies Japan, 1996: 101–6

Hoffmann C, Zschiesche M, Franke G, et al. Single and multiple dose bioavailability study with carbamazepine 400 mg retard tablets with reference to enzyme autoinduction and circadian time differences. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther Toxicol 1997; 35(11): 496–503

Jackson AJ. Prediction of steady state bioequivalence relationships using single dose data I linear kinetics. Biopharm Drug Dispos 1987; 8(5): 483–96

el-Tahtawy AA, Jackson AJ, Ludden TM. Comparison ofsingle and multiple dose pharmacokinetics using clinical bioequivalence data and Monte Carlo simulations. Pharm Res 1994; 11(9): 1330–6

el-Tahtawy A, Jackson AJ, Ludden TM. Evaluation of bioequivalence of highly variable drugs using Monte Carlo simulations: part 1. Estimation of rate of absorption for single and multiple dose trials using Cmax. Pharm Res 1995; 12(11): 1634–41

el-Tahtawy AA, Tozer TN, Harrison F, et al. Evaluation of bioequivalence of highly variable drugs using clinical trial simulations: II. Comparison of single and multiple-dose trials using AUC and Cmax. Pharm Res 1998; 15(1): 98–104

Zha J, Endrenyi L. Variation of the peak concentration following single and repeated drug administrations in investigations of bioavailability and bioequivalence. J Biopharm Stat 1997; 7(1): 191–204

Tothfalusi L, Endrenyi L. Estimation of Cmax and Tmax in populations after single and multiple drug administrations. J Pharmacokin Pharmacodyn 2003; 30(5): 363–85

Endrenyi L, Fritsch S, Yan W. Cmax/AUC is a clearer measure than Cmax for absorption rates in investigations of bioequivalence. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther Toxicol 1991; 29: 394–9

Elze M, Potthast H, Blume HH. Metrics of absorption: data base analysis. In: Blume HH, Midha KK, editors. Bio-International 2: bioavailability, bioequivalence and pharmacokinetics. Stuttgart: Medpharm, 1995: 61–71

Lacey LF, Keene ON, Duquesnoy C, et al. Evaluation of different indirect measures of rate of drug absorption in comparative pharmacokinetic studies. J Pharm Sci 1994;83:212–5

Schall R, Luus HG, Steinijans VW, et al. Choice of characteristics and their bioequivalence ranges for the comparison of absorption rates of immediate-release drug formulations. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther 1994; 32: 323–8

Tothfalusi L, Endrenyi L. Without extrapolation, Cmax/AUC is an effective metric in investigations of bioequivalence. Pharm Res 1995; 12(6): 937–42

Bois FY, Tozer TN, Hauck WW, et al. Bioequivalence: performance of several measures of rate of absorption. Pharm Res 1994; 11(7): 966–74

Endrenyi L, Csizmadia F, Tothfalusi L, et al. Metrics comparing simulated early concentration profiles for the determination of bioequivalence. Pharm Res 1998; 15(8): 1292–9

Chen ML. An alternative approach for assessment of rate of absorption in bioequivalence studies. Pharm Res 1992; 9(11): 1380–5

Rostami-Hodjegan A, Tucker GT. Comment: is Cmax/AUC useful for bioequivalence testing? J Pharm Sci 1997; 86(3): 401–2

Tozer TN, Hauck WW. Cmax/AUC, a commentary. Pharm Res 1997; 14(8): 967–8

Chen ML, Lesko LJ. Individual bioequivalence revisited. Clin Pharmacokinet 2001; 40(10): 701–6

Schall R. Assessment of individual and population bioequivalence using the probability that bioavailabilities are similar. Biometrics 1995; 51(2): 615–26

Patnaik RN, Lesko LJ, Chen ML, et al. Individual bioequivalence: new concepts in the statistical assessment of bioequivalence metrics. Clin Pharmacokinet 1997; 33: 1–6

Boddy AW, Snikeris FC, Kringle RO, et al. An approach for widening the bioequivalence acceptance limits in the case of highly variable drugs. Pharm Res 1995; 12(12): 1865–8

Schall R. A unified view of individual, population, and average bioequivalence. In: Blume H, Midha K, editors. Bio-International 2: bioavailability, bioequivalence and pharmacokinetics. Stuttgart: Medpharm, 1995: 91–106

Tothfalusi L, Endrenyi L, Midha K, et al. Evaluation ofthe bioequivalence of highly-variable drugs and drug products. Pharm Res 2001; 18(6): 728–33

Lionberger RA, Lee SL, Lee L, et al. Quality by design: concepts for ANDAs. AAPS J 2008; 10(2): 268–76

Haidar SH, Makhlouf F, Schuirmann DJ, et al. Evaluation of a scaling approach for the bioequivalence of highly variable drugs. AAPS J 2008; 10(3): 450–4

Ormsby E. International experience on BE practice: Canada. Bio-International 2008. London: International Pharmaceutical Federation (FIP), 2008

Walker RB, Kanfer I, Skinner MF. Bioequivalence assessment of generic products: an innovative South African approach. Clin Res Regul Affairs 2006; 23(1): 11–20

European Medicines Agency [EMEA] Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use [CHMP]. Draft guideline on the investigation of bioequivalence [document reference CPMP/EWP/QWP/1401/98 Rev. 1]. London: EMEA, 2008 [online]. Available from URL: http://www.emea.europa.eu/pdfs/human/qwp/140198enrev1.pdf [Accessed 2008 Nov 17]

Salmonson T. Revision of the CPMP note for guidance: legal basis and regulatory needs. European Federation for Pharmaceutical Sciences [EUFEPS] Bioavailability and Biopharmaceutics [BABP] Network Conference 2009; 2009 Jan 14–15; Bonn

Steinijans VW. Some conceptual issues in the evaluation of average, population, and individual bioequivalence. Drug Information J 2001; 35(3): 893–9

Vuorinen J, Turunen J. A three-step procedure for assessing bioequivalence in the general mixed-model framework. Stat Med 1996; 15: 2635–55

Wellek S. On a reasonable disaggregate criterion of population bioequivalence admitting of resampling-free testing procedures. Stat Med 2000; 19(20): 2755–67

Chow SC, Liu JP. Design and analysis of bioavailability and bioequivalence studies. 3rd ed. New York: Chapman & Hall/CRC, 2008

Patterson S, Jones B. Bioequivalence and statistics in clinical pharmacology. Boca Raton (FL), London: Chapman & Hall/CRC, 2006

Tothfalusi L, Endrenyi L. Limits for the scaled average bioequivalence of highly variable drugs and drug products. Pharm Res 2003; 20(3): 382–9

Tothfalusi L, Endrenyi L, Midha KK. Scaling or wider bioequivalence limits for highly variable drugs and for the special case of Cmax. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther 2003; 41(5): 217–25

Dragalin V, Fedorov V, Patterson S, et al. Kullback-Leibler divergence for evaluating bioequivalence. Stat Med 2003; 22(6): 913–30

Steiger JH. Beyond the F test: effect size confidence intervals and tests of close fit in the analysis of variance and contrast analysis. Psychol Meth 2004; 9: 164–82

Cumming G, Finch S. A primer on the understanding, use, and calculation of confidence intervals that are based on central and noncentral distributions. Educ Psychol Meas 2001; 61: 532–74

Chan LK, Cheng SW, Spiring FA. New measure ofprocess capability: Cpm. J Qual Technol 1989; 20(3): 162–75

Feinstein AR. Indexes of contrast and quantitative significance for comparisons of two groups. Stat Med 1999; 18(19): 2557–81

Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. New York: Academic Press, 1969

Borenstein M. Hypothesis testing and effect size estimation in clinical trials. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 1997; 78(1): 5–11

Tritchler D. Interpreting the standardized difference. Biometrics 1995; 51(1): 351–3

Endrenyi L, Tothfalusi L. Regulatory conditions for the determination of bioequivalence of highly variable drugs. J Pharm Pharmaceut Sci 2009; 12(1): 138–49

Chow SC. Statistical considerations for replicated designs. In: Midha KK, Nagai T, editors. Bioavailability, bioequivalence and pharmacokinetic studies: FIP Bio-International ′96 (1996 Tokyo, Japan). Tokyo: Business Center for Academic Societies Japan, 1996: 107–12

Karim A, Zhao Z, Slater M, et al. Replicate study design in bioequivalency assessment, pros and cons: bioavailabilities of the antidiabetic drugs pioglitazone and glimepiride present in a fixed-dose combination formulation. Clin Pharmacol 2007; 47(7): 808–16

Midha KK, Rawson M, Hubbard JW, et al. Practical strategies and design advantages for highly variable drugs: replicate design. In: Blume HH, Midha KK, editors. Bio-International 2: bioavailability, bioequivalence and pharmacokinetics. Stuttgart: Medpharm, 1995: 123–8

Patterson SD, Zariffa NM, Montague TH, et al. Non-traditional study designs to demonstrate average bioequivalence for highly variable drug products. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2001; 57(9): 663–70

Gould AL. A practical approach for evaluating population and individual bioequivalence. Stat Med 2000; 19: 2721–40

Chen ML, Lee SC, Ng MJ, et al. Pharmacokinetic analysis of bioequivalence trials: implications for sex-related issues in clinical pharmacology and bio-pharmaceutics. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2000; 68(5): 510–21

Chow SC, Shao J, Wang H. Individual bioequivalence testing under 2 × 3 designs. Stat Med 2002; 21(5): 629–48

Endrenyi L, Taback N, Tothfalusi L. Properties of the estimated variance component for subject-by-formulation interaction in studies of individual bioequivalence. Stat Med 2000; 19(20): 2867–78

Guilbaud O. Exact inference about the within-subject variance in 2 × 2 crossover studies. J Am Stat Assoc 1993; 88: 939–46

Guilbaud O. Exact comparisons of means and variances in 2 × 2 cross-over trials. Drug Info J 1999; 33: 455–69

Jiang G, Sarkar SK. Comparing treatment variances in repeated measures bioavailabilitytrials. Stat Med 1999; 18: 1133–49

Wang W. Optimal unbiased tests for equivalence in intrasubject variability. J Am Stat Assoc 1997; 92: 1163–70

Hyslop T, Hsuan F, Holder DJ. A small sample confidence interval approach to assess individual bioequivalence. Stat Med 2000; 19(20): 2885–97

Howe W. Approximate confidence limits on the mean of X + Y where X and Y are two tabled independent random variables. J Am Stat Assoc 1974; 69: 789–94

Endrenyi L, Tothfalusi L. Evaluation of bioequivalence of highly variable drugs. In: Kanfer I, Shargel L, editors. Generic drug product development bioequivalence issues. New York: Informa, 2008: 97–117

Patterson SD, Jones B. Bioequivalence and the pharmaceutical industry. Pharm Stat 2002; 1: 83–95

Willavize SA, Morgenthien EA. Comparison of models for average bioequi valence in replicated crossover designs. Pharm Stat 2006; 5(3): 201–11

Hsuan FC, Reeve R. Assessing individual bioequivalence with high-order cross-over designs: a unified procedure. Stat Med 2003; 22(18): 2847–60

Kovarik JM, Mueller EA, Van Bree JB, et al. Reduced inter- and intra- individual variability in cyclosporine pharmacokinetics from a microemulsion formulation. J Pharm Sci 1994; 83: 444–6

Karalis V, Symillides M, Macheras P. Novel scaled average bioequivalence limits based on GMR and variability considerations. Pharm Res 2004; 21(10): 1933–42

Karalis V, Macheras P, Symillides M. Geometric mean ratio-dependent scaled bioequivalence limits with leveling-off properties. Eur J Pharm Sci 2005; 26(1): 54–61

Karalis V, Macheras P, Van Peer A, et al. Bioavailability and bioequivalence: focus on physiological factors and variability. Pharm Res 2008; 25(8): 1956–62

Karalis V, Symillides M, Macheras P. Comparison of the reference scaled bioequivalence semi-replicate method with other approaches: focus on human exposure to drugs. Eur J Pharm Sci 2009; 38(1): 55–63

Kytariolos J, Karalis V, Macheras P, et al. Novel scaled bioequivalence limits with leveling-off properties. Pharm Res 2006; 23(11): 2657–64

Cartwright A, Gundert-Remy W, Rauws G, et al. International harmonization and consensus DIA meeting on bioavailability and bioequivalence testing requirements and standards. Drug Info J 1991; 25: 471–82

Midha KK, Shah VP, Singh GJ, et al. Conference report: Bio-International 2005. Pharm Sci 2007; 96(4): 747–54

Midha KK, Nagai T, Blume HH, et al. Conference report: Bio-International ′96. In: Midha KK, Nagai T, editors. Bioavailability, bioequivalence and pharmacokinetic studies: FIP Bio-International ′96 (1996 Tokyo, Japan). Tokyo: Business Center for Academic Societies Japan, 1996: 1–8

Acknowledgements

The views expressed by Alfredo Garcia Arieta in this article represent his personal opinion and may not represent necessarily the policy or recommendations of the Spanish Agency for Medicines and Health Care Products. No sources of funding were used to assist in the preparation of this review. The authors have no conflicts of interest that are directly relevant to the content of this review.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tothfalusi, L., Endrenyi, L. & Arieta, A.G. Evaluation of Bioequivalence for Highly Variable Drugs with Scaled Average Bioequivalence. Clin Pharmacokinet 48, 725–743 (2009). https://doi.org/10.2165/11318040-000000000-00000

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2165/11318040-000000000-00000